Saga and Process Manager - distributed processes in practice

What can go wrong with distributed systems?

Everything!

I like to compare distributed systems to Rocky Balboa fighting the last round with Apollo Creed. He is staggering on his feet. His face is bruised, left hand is hanging, his eyes are black. Rocky is struggling but still pushing forward. And that’s good! On the other hand, the monoliths are standing firmly until the fight starts. However, when Monolith get a shot, it usually ends up with the KO.

There were times when I thought that I can have control over the distributed environment. I tried to configure distributed transactions using WCF and MSDTC (if you don’t know any of these acronyms then be happy and don’t even google them). I succeeded in a way that it was sometimes working. Usually, it was not.

Why are distributed transactions so difficult or even impossible to achieve?

It’s hard because at any given point in time:

- all services must be available and responsive,

- the coordinator that manages the transaction must always be available to process individual operations,

- it must be fast enough to stop a large queue forming.

If we also add:

- deadlocks can be problems even in regular transactions,

- maintaining the appropriate transaction isolation levels is difficult even for one service,

- in case of an error in one service, we have to roll back changes made on other participants.

All this makes distributed transactions Peter Buckley type of fighter. They should not go into a real production battle.

So what are the alternatives?

- Saga,

- Process Manager,

- Choreography.

All three basically boil down to one principle: do it yourself. We do not use any particular technology to manage transactions. So how does it work?

The first step is to write out the process. It can look like that:

- The customer initiates the shopping cart.

- Adds products to it.

- Confirms the purchase.

- At this point, the order process begins.

- The first step is to pay for the selected products.

- If it is successful, the order changes its status to paid, and we start the shipment process.

- If the shipment is successful, we mark the order as completed.

What if one of the operations fails?

- If the payment fails, we will cancel the order.

- When the shipment fails (e.g. because the product is no longer available), we cancel the credit card charge if it’s possible. If not then we’re sending a request to refund.

Of course, the described process is simplistic. It’s like that to focus on the concept rather than the specific business case.

The next step is to determine which module/service should handle each step of the process. We can divide it, for example, between modules:

- shopping cart management,

- orders,

- payments,

- shipment.

Well, now we really need to:

- Define the events that occur in the process, e.g. the basket is confirmed, products paid, products shipped.

- Define requests (commands) that cause them, e.g. start an order, pay for products, send products).

Having commands and corresponding events, we can build a “sandwich” - action => reaction, command => event.

As we have the process written out and divided into modules, we can determine where we can run local transactions. Usually, within one module, primarily if we use relational databases, we can have transactions. Why? Because we typically have one database.

That is why, in fact, instead of making one large distributed transaction, we create a flow consisting of many small transactions. Each module should take care of the correct handling and notify others that the operation was successful or not.

How does it do this? Preferably through an event. So if we managed to send the package, we trigger an event. If there is no product in the warehouse, we send an event that the parcel could not be sent. If we send events over a durable message bus (such as Kafka or RabbitMQ), we get an even greater fault-tolerance. If a given service is temporarily unavailable, the process will not fail. When the service comes back to life, it will handle the event.

Of course, you can send commands synchronously. You can use in-memory buses. It depends on us how strong the reliability guarantees we want to provide. I’d recommend finding those constraints from the business and then choosing the tools based on them.

An important thing to note is that we have to avoid the workflow freezing during the processing. How do we achieve that?

- Wrap the entire command handler in try/catch, and send back a failure event.

- This will not protect us by 100%. It is always worth having a background worker that will send an event when the maximum processing time was reached. Thus we can cancel it.

- We should think of the compensation procedure triggered manually. It’ll be an ace up our sleeve when other methods fail.

Let’s get back to Sagas etc. We can divide the coordination into two main approaches:

- Orchestration, where one service works as a conductor and drives it all via waving of a baton,

- Choreography, when the services react to each other’s operations.

The advantage of choreography is that we do not have the so-called “single point of failure”. We have an orchestra that may continue to play without a conductor. The downside is that we have a fragmented process that is difficult to grasp. From the perspective of a programmer of one module developer, we know that when we get such a command, we have to send such an event, etc.

It’s excellent for the more straightforward scenarios, as it cuts complexity. For more complex cases, it is crucial to know the big picture of the process. Without it, it’s hard to manage it. We need to remember that business is not interested in our internal technical split. They are interested in the end result, i.e. the smooth operation of the workflow.

Orchestration brings coupling, but sometimes it’s good as it shapes the precise boundaries of responsibility. That helps with coordination.

Saga and Process Manager are examples of coordination.

The term saga comes from the “SAGAS” whitepaper written in 1987 by Hector Garcia-Molina and Kenneth Salem (https://www.cs.cornell.edu/andru/cs711/2002fa/reading/sagas.pdf). It describes it as the solution for the Long Lived Transactions (LLT).

“A LLT is a saga if it can be written as a sequence of transactions that can be interleaved with other transactions. The database management system guarantees that either all the transactions in a saga are successfully completed or compensating transactions are run to amend a partial execution”

A saga doesn’t have to know where the event comes from and where the command is going. It is basically a “stupid” coordinator/dispatcher who:

- Waits for the event.

- When a success event arrives, dispatches a command based on the event data (and only this data).

- When a failure event arrives, send the command to start compensation (e.g. refund the payment). It’s important to know that a saga should support the “rollback” of all the actions that happened before the failure event was recorded.

Thanks to this, a saga is lightweight. It can be put into the module together with other logic. It can also be pulled out to a separate one.

This is what makes Saga different from Process Manager. The Saga itself has no state. A Process Manager can be modelled as a state machine. It makes decisions based not only on incoming events but also the current state of the process.

For me, this distinction is essential. The “stupid” Saga is much more flexible and gives less overhead than a Process Manager. There are just fewer places where something can go wrong. So unless I have a really complex workflow, I’d try to avoid using a Process Manager.

How to use Saga when data from the event is not enough? We’re getting into a dangerous area, but we must go on.

We can get a little help from an aggregate (e.g. Order, for the process described above). For example, after the payment is completed, we should send the ordered product. Payment Completed event does not contain any information about a specific product: it only carries information about how much you have to pay. Though, we have this data in the order aggregate. As we need to mark the order state as paid, then we can send such a command. The saga listens for an event confirming the order status change. Such an event will have the needed information about order and the saga can proceed with sending the shipment command. Of course, this is a bit of a “trick”. Someone might say it’s an implicit Process Manager, but in my opinion, it is a simple, pragmatic rule showing how you can create stateless sagas.

Sample saga in pseudocode looks like:

class OrderSaga

{

// Happy path

void Handle(CartFinalized event)

{

SendCommand(

new InitOrder(

event.CartId, event.ClientId, event.ProductItems, event.TotalPrice

)

);

}

void Handle(OrderInitialized event)

{

SendCommand(

new RequestPayment(

event.OrderId, event.TotalPrice

)

);

}

public void Handle(PaymentFinalized event)

{

SendCommand(

new RecordOrderPayment(

event.OrderId, event.PaymentId, event.FinalizedAt

)

);

}

void Handle(OrderPaymentRecorded event)

{

SendCommand(

new SendPackage(

event.OrderId, event.ProductItems

)

);

}

void Handle(PackageWasSent event)

{

SendCommand(

new CompleteOrder(

event.OrderId

)

);

}

// Compensation

void Handle(ProductWasOutOfStock event)

{

SendCommand(

new CancelOrder(

event.OrderId, OrderCancellationReason.ProductWasOutOfStock

)

);

}

void Handle(OrderCancelled event)

{

SendCommand(

new DiscardPayment(

event.PaymentId.Value

)

);

}

}I recommend to also read my post about the delivery guarantees to know how to make sure that all events and commands will be delivered.

You can also check the real implementation written in C#:

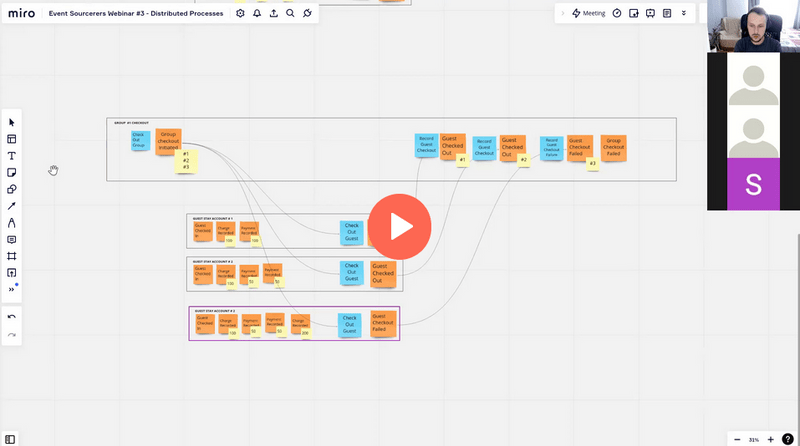

I explained also how to model distributed processes in detail in the webinar about implementing distributed processes:

Additionally, I have prepared a set of recommended materials about distributed processes, read more.

Read also more in:

- Event-driven distributed processes by example.

- Oops I did it again, or how to update past data in Event Sourcing,

- Set up OpenTelemetry with Event Sourcing and Marten,

- Set of recommended materials about distributed processes.

Cheers!

Oskar