Not all issues are complex, some are complicated. Here's how to deal with them

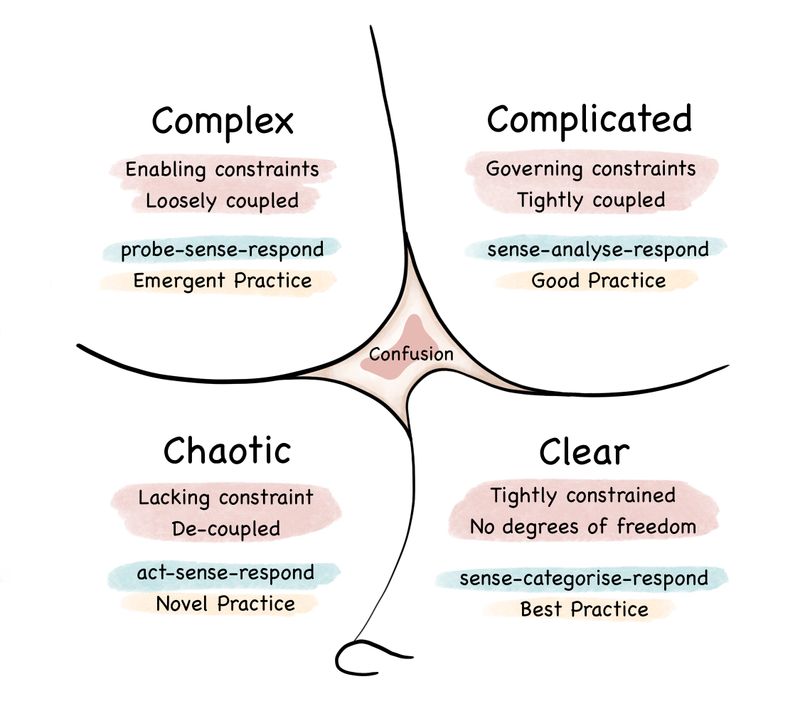

Cynefin’s framework states that we have four types of decision-making contexts (or domains): clear, complicated, complex, and chaotic. They also add confusion to the mix. And that sounds like a fair categorisation of the problems we face.

Clear issues we solve on autopilot, chaotic ones we tend to ignore, and complex ones sound like a nice challenge. And complicated problems? We call them tedious.

Complex problems are called unknown unknowns. This is the place where we feel creative; we do an explorer job. We probe sense and respond. The design emerges and Agile shines. We solve it, and then we go further into the sunset scenery like a lonesome cowboy. Off we go to the next exciting problem.

Complicated issues, on the other hand, are known unknowns. They represent something that has to be done. If we have the expertise, we can sense it with our educated gut feeling, analyse it and respond with a solution. In other words, we usually know what we need to do, but we need to find an exact how to solve it. Unknowns are more tactical than strategic.

And here’s the funny thing: we too often feel more comfortable solving complex tasks than complicated ones. We counterintuitively think, “Well, we just need to do research, then select a solution and solve it”. Too often, that’s our self-defence. We’re tricking ourselves by postponing the issue. It’s easier to justify our efforts in research than lag on known unknowns.

If we categorise something as complex, then probably no one from our close circle knows the answer. There’s less chance that we’ll be criticised. For complicated, there’s a feeling that someone can always come and say “It is an easy task; why are you spending so much time on it?”. Yes, complicated is a subjective term. It’s like an inverted Instant Gratification Theory; we’re delaying potential bad scenarios.

Some say that complex tasks will give more benefits, as only a few people can solve them. That’s partially true, but there’s also a reason why they’re complex, and we don’t know if we’re that person able to solve it. As I mentioned, we tend to downplay complex problems, and accidental complexity kills our efforts.

We already learned that complicated tasks are perceived as boring, and we tend to avoid them. They usually reflect those annoying bugs killing our product by 1000 paper cuts.

Let’s say that we have two tasks to choose from. One is complex, and the other is complicated. They both have a similar business value. Shouldn’t we choose the one with known unknowns?

Let’s say we should, but how do we tackle complicated tasks? I’ll show you how I did it with the example.

Marten is the open-source project I’m working on. It allows using PostgreSQL as a Document Database and Event Store. Our goal is to help remove boilerplate work. Thus, we provide multiple ways of dealing with multitenancy out of the box. We have two major options with tenant column in each table level, database per tenant if you need complete data separation. We’ll discuss the issue with the first option.

With Marten, you can do the following code to configure Marten to use the basic tenancy on the table level:

var store = DocumentStore.For(options =>

{

options.Connection("some connection string");

// The events are now multi-tenanted

options.Events.TenancyStyle = TenancyStyle.Conjoined;

// And all documents also

options.Policies.AllDocumentsAreMultiTenanted();

});It’ll define the TenantId column for events and each document table. It’ll be used to discriminate all operations, so you accidentally won’t change data from another tenant.

You can set up a session for the tenant as follows:

await using var session = store.OpenSession("SomeTenantId");Then, all operations will include this tenant id as an additional parameter.

And that’s the perfect world; the reality is much more complicated..

For instance, you’re building a SaaS platform like Booking.com. Almost all data will be specific for tenants, but you have some global data that can use various tenants; for instance, users can book nights in multiple hotel chains. You might also want to have global reports showing all tenants’ aggregations.

Moreover, some may have admin operations that should update data from multiple tenants.

Of course, being an Open Source maintainer, you may ignore such feature requests and not provide support; that’s some solution. But if you want to keep your community thriving and your tool helping users, you accept such feature requests.

Some time ago, we provided the option to create a nested session for different tenants. You could, for instance, do the following code:

// Create a global session with no tenant

await using var session = store.OpenSession();

// Create user globally

session.Events.Append(new UserRegistered(userId));

// Create a nested session for the tenant

var nestedSession = session.ForTenant(hotelChainId);

nestedSession.Events.Append(new RoomReserved(roomId, hotelId, userId));

await session.SaveChangesAsync();That looks simple enough; indeed, it’s not extremely complicated if we consider only writes. Marten has built-in Unit of Work, which stores all pending changes in the same transactions. In the case above, it’ll append the UserRegistered event as global data (using default tenant) and RoomReserved to the hotel chain tenant.

Stuff gets more complex if we consider projections. Marten can build read models based on the stored events (read more in Event-driven projections in Marten explained). Projections can be inline and async. Inline is run within the same transaction as appended events, and async is the background process. And now, things start to get complicated:

- an event can update multiple projections,

- an event with a default tenant can update projections with a default tenant (so global data). (We don’t support updating tenants based on the global data, as this could create a ripple effect).

- an event with a non-default tenant can update projections with non-default and default tenants. The last one helps in global summaries (e.g., a report of the number of reservations from all chains).

- a single unit of work can have events from multiple tenants (both default and non-default).

Not complicated enough? Be my guest! Async projections are a fancy beast. We want to make the processing efficient, so we optimise them. Each projection type (e.g. UserProfileDetails, RoomReservation, etc.) is processed in parallel. We poll batches of events for each projection type based on the event types it supports. Thanks to that, we only read needed events and limit the number of queries. We’re also grouping events by tenant id and the read model id. Thanks to that, if there are a few events in the batch updating a single read model, we’ll load it only once, apply those events, and store the result as a single update statement. And that’s just a brief description of our optimisations and potential permutations.

Coming back to our multitenancy and its impact on async projections. If we group events by tenant, we’re grouping them based on the tenant it was appended to (e.g. hotel chain id or default one). That’s fine for primary usage, but you already know that the read model can have different tenants than the events (e.g. global reports). For such a case, we must open a nested session. And one of our users spotted inconsistency. Gulp.

I realised that such an approach requires a systematic approach. If I just tried to sit and fix it, then my work would look like in this famous Peter Griffin scene:

To have that under control, I needed:

- write up the permutations,

- have the centralised code for deciding whether to open nested session or not,

- have that code unit-testable, and write clear tests for that.

The best way to write up permutations is to write them up in table. I did it like that:

|---------------------------------------------------------|

| SCENARIOS |

|---------------------------------------------------------|

| SESSION | SLICE | STORAGE | RESULT |

|-------------|-------------|-----------|-----------------|

| DEFAULT | DEFAULT | SINGLE | THE SAME |

| DEFAULT | DEFAULT | CONJOINED | THE SAME |

| DEFAULT | NON-DEFAULT | SINGLE | THE SAME |

| DEFAULT | NON-DEFAULT | CONJOINED | NEW NON-DEFAULT |

| NON-DEFAULT | DEFAULT | SINGLE | NEW DEFAULT |

| NON-DEFAULT | DEFAULT | CONJOINED | THE SAME |

| NON-DEFAULT | NON-DEFAULT | SINGLE | NEW DEFAULT |

| NON-DEFAULT | NON-DEFAULT | CONJOINED | THE SAME |Where:

- Session - original processing session tenancy (default tenant or non-default)

- Slice - the tenancy of grouped batch of events (default tenant or non-default)

- Storage - the tenancy of the read model (Single - only default tenant is allowed, Conjoined - non-default tenants are allowed).

- Result - either the same session can be used, or a new nested one should be created (with default or non-default tenant).

You can also see a pattern in which I described permutations. I started by adding possible values for the first column (DEFAULT and NON-DEFAULT), then for each value, I added the permutations for the second column and then did the same for the third column. Thanks to that, I’m sure that I covered all permutations. It’s also easier to read and reason if we see bigger groups first and then smaller subgroups in the following columns.

Having all permutations, I filled in the result. That’s the part that cannot be done automatically. You need to sit and think of the expected result based on the constraints you have. If it’s about complicated business logic, then it’s time to consult your domain expert to ensure that you understand that well. Once you confirm it, such a breakdown will be an excellent input for unit tests.

Preparing a permutations table sounds straightforward, but it does not always have to be like that. We might get so many permutations or additional edge case constraints that such a table would be too big to give clear answers. The art in that is to decide which scenarios are essential and which are edgy. In my case, I decided to ignore some conditions like feature flags defining whether we allow multi-tenancy, global projections, and if we should keep tenants in the same database (we also allow database per tenant). Of course, I’ll need to include them in the final implementation and the set of test scenarios, but they’re not changing the big picture; they’re switching some settings. Adding them to the permutations table would blur the picture and not help enhance understanding.

Based on that, I prepared the implementation:

internal static class TenantedSessionFactory

{

// I also placed permutation table here as a comment,

// but skipped it in this snippet for brevity

internal static DocumentSessionBase UseTenancyBasedOnSliceAndStorage(

this DocumentSessionBase session,

IDocumentStorage storage,

IEventSlice slice

)

{

var shouldApplyConjoinedTenancy =

session.TenantId != slice.Tenant.TenantId

&& slice.Tenant.TenantId != Tenancy.DefaultTenantId

&& storage.TenancyStyle == TenancyStyle.Conjoined

&& session.DocumentStore.Options.Tenancy.IsTenantStoredInCurrentDatabase(

session.Database,

slice.Tenant.TenantId

);

if (shouldApplyConjoinedTenancy)

return session.WithTenant(slice.Tenant.TenantId);

var isDefaultTenantAllowed =

session.SessionOptions.AllowAnyTenant

|| session.Options.Advanced.DefaultTenantUsageEnabled;

var shouldApplyDefaultTenancy =

isDefaultTenantAllowed

&& session.TenantId != Tenancy.DefaultTenantId

&& storage.TenancyStyle == TenancyStyle.Single;

if (shouldApplyDefaultTenancy)

return session.WithDefaultTenant();

return session;

}

private static DocumentSessionBase WithTenant(this IDocumentSession session, string tenantId) =>

(DocumentSessionBase)session.ForTenant(tenantId);

private static DocumentSessionBase WithDefaultTenant(this IDocumentSession session) =>

(DocumentSessionBase)session.ForTenant(Tenancy.DefaultTenantId);

}As you see, there are some weird ifs; I told you it’s complicated. Still, it’s manageable and much more straightforward than it could be, especially if we keep the permutation table together with the code. That’s actually good example of the helpful comment in code.

I also added potentially redundant wrappers WithTenant and WithDefaultTenant. They’re just wrapping single-line code calls, but I wanted to highlight the intention explicitly. The same I did for additional variables like shouldApplyConjoinedTenancy, isDefaultTenantAllowed, and shouldApplyDefaultTenancy. I could probably zip it more, but thanks to them, when reading code for the first time, you might not need to understand those weird ifs fully, but read what they’re checking thanks to clear variable names.

I also used inverted ifs. Instead of nesting else conditions, I’m returning the result as fast as possible. In such an approach, the important part is keeping the default, expected option as the last. In our case, that’s reusing existing sessions, and that’s reflected in the code. That also helps the reader, as they can first scroll down to see what, by default, is returned and then check edge cases.

Yes, I didn’t write tests first. I have to confess that I never got fully into the habit of doing that. Usually, I start with a raw draft of the API, and then I do the red/green sandwich. I feel more efficient by doing that, especially when I need surgery on already existing, complicated code. Still, if you prefer to follow fully TDD, that’s also a viable option.

I also wanted tests to be explicit about the intention. If we have such repeatable code varying on the permutation of inputs, it’s good to do Property-based testing. So, preparing (or generating) a set of inputs ensures that they give an expected result. In Marten, we’re using the XUnit framework, which allows us to do it through Theory attribute. Sidenote: that’s not precisely property-based testing (more parametrised test), as we’re manually setting the values instead of letting the testing framework do that. Yet, the intention is the same. We’re testing specific properties of our system by providing different sets of values testing various paths of the same flow.

public class TenantedSessionFactoryTests

{

// here I also placed permutation table as comment

[Theory]

[MemberData(nameof(Configurations))]

public void Verify(Configuration setup)

{

// Given

var session = SessionWith(setup);

var slice = SliceWith(setup);

var storage = StorageWith(setup);

// When

var newSession = session.UseTenancyBasedOnSliceAndStorage(storage, slice);

// Then

if (!setup.ExpectsNewSession)

{

newSession.ShouldBe(session);

}

else

{

newSession.ShouldNotBe(session);

newSession.ShouldBeOfType<NestedTenantSession>();

newSession.TenantId.ShouldBe(setup.ExpectedNewSessionTenantId);

}

}

public static TheoryData<Configuration> Configurations =>

new()

{

// (...) wait for that

}

}Thanks to that, the test code is the same. We’re building the inputs based on the configuration and then checking if we got the expected result.

Beware here not to fall into a trap providing the test for everything. Such an approach is tempting to overgeneralise testing scenarios. I’ve used a single test method here, as my code is just effectively making a single decision: use an existing session or create a new one. The code is not complex but complicated because of the permutations of the input and conditional logic. If you have more scenarios, express each scenario in the dedicated test. In the past, I felt the trap and abused this approach, ending with tests that would require tests to verify that they’re testing code correctly… Beware, and don’t go down that path. Tests are a form of documentation, and duplication is, in general, okay for them.

Let’s check how the test configuration is setup:

public static TheoryData<Configuration> Configurations =>

new()

{

TheSame(Default, Default, TenancyStyle.Single),

TheSame(Default, Default, TenancyStyle.Conjoined),

TheSame(Default, NonDefault, TenancyStyle.Single),

New(Default, NonDefault, TenancyStyle.Conjoined, NonDefault),

TheSame(Default, NonDefault, TenancyStyle.Conjoined,

isTenantStoredInCurrentDatabase: false

),

New(NonDefault, Default, TenancyStyle.Single, Default),

New(NonDefault, Default, TenancyStyle.Single, Default,

allowAnyTenant: false,

defaultTenantUsageEnabled: true

),

New(NonDefault, Default, TenancyStyle.Single, Default,

allowAnyTenant: true,

defaultTenantUsageEnabled: false

),

TheSame(NonDefault, Default, TenancyStyle.Single,

allowAnyTenant: false,

defaultTenantUsageEnabled: false

),

TheSame(NonDefault, Default, TenancyStyle.Conjoined),

New(NonDefault, NonDefault, TenancyStyle.Single, Default),

New(NonDefault, NonDefault, TenancyStyle.Single, Default,

allowAnyTenant: false,

defaultTenantUsageEnabled: true

),

New(NonDefault, NonDefault, TenancyStyle.Single, Default,

allowAnyTenant: true,

defaultTenantUsageEnabled: false

),

TheSame(NonDefault, NonDefault, TenancyStyle.Single,

allowAnyTenant: false,

defaultTenantUsageEnabled: false

),

TheSame(NonDefault, NonDefault, TenancyStyle.Conjoined),

};Each row will run as a separate test with the provided configuration. I provided firstly the expected result, so TheSame or New session. Then, I’m passing additional configuration. The first three params come directly from our permutation table and optional params (allowAnyTenant, defaultTenantUsageEnabled) from those edge casy feature flags.

The configuration is encapsulated into a dedicated configuration class, and TheSame and New are static factory methods preparing it. I added them to make the setup explicit and encapsulate it.

public record Configuration(

string SessionTenant,

string SliceTenant,

TenancyStyle StorageTenancyStyle,

bool IsTenantStoredInCurrentDatabase,

bool AllowAnyTenant,

bool DefaultTenantUsageEnabled,

bool ExpectsNewSession,

string? ExpectedNewSessionTenantId = default

)

{

public static Configuration TheSame(

string sessionTenant,

string sliceTenant,

TenancyStyle storageTenancyStyle,

bool isTenantStoredInCurrentDatabase = true,

bool allowAnyTenant = true,

bool defaultTenantUsageEnabled = true

) => new(

sessionTenant,

sliceTenant,

storageTenancyStyle,

isTenantStoredInCurrentDatabase,

allowAnyTenant,

defaultTenantUsageEnabled,

false);

public static Configuration New(

string sessionTenant,

string sliceTenant,

TenancyStyle storageTenancyStyle,

string? expectedNewSessionTenantId,

bool allowAnyTenant = true,

bool defaultTenantUsageEnabled = true

) => new(

sessionTenant,

sliceTenant,

storageTenancyStyle,

true,

allowAnyTenant,

defaultTenantUsageEnabled,

true,

expectedNewSessionTenantId

);

}Of course, you may come up with other implementations. You may feel that it’s still not readable enough, and that’s fine. I want to give you the thought process and tools to reason with complicated problems; the implementation details may differ based on your preferences, the tools you use and the language you code.

That’s also why I used the real scenario from the real project. It’s dirty and filled with tradeoffs, as complicated scenarios are. See the full code in the Pull Request. It shows the complete scope of changes and all tests I added/updated. Plus, dirty stuff like mocking abstract class. You cannot fix the whole word with one change.

And here are two final pieces of advice.

Don’t try to refactor together with complicated changes. Kent Beck said: “Make the change easy, make the easy change”. You’ll increase the accidental complexity if you try to perform broad refactoring and apply complicated changes. Such an approach usually ends up in a long-living branch that will never get merged. Don’t do that. Limit the scope of change; either do refactoring first or afterwards. Not at the same time.

Even with the best, methodic approach, you may miss something and make a mistake. What I described here helps to organise your thoughts, analyse the complicated scenario and make it more predictable. Yet, with the complicated problems and bigger existing codebase, we can still miss something. So do your best, but prepare for failure. What I described above was a decent solution, but not perfect. I missed one permutation and didn’t apply that everywhere; luckily, one of the users spotted it and provided the fix. The good thing was that I made the change easy, as my previous work could be reused and test scenarios expanded.

Cheers!

Oskar

p.s. Ukraine is still under brutal Russian invasion. A lot of Ukrainian people are hurt, without shelter and need help. You can help in various ways, for instance, directly helping refugees, spreading awareness, putting pressure on your local government or companies. You can also support Ukraine by donating e.g. to Red Cross, Ukraine humanitarian organisation or donate Ambulances for Ukraine.