Outbox, Inbox patterns and delivery guarantees explained

Yesterday I was asked by Cezary about the transactional outbox pattern sample implementation.

Looking for an example implementation of Transactional Outbox Pattern with #SqlServer Transaction log tailing in #dotnet. Any existing libraries for that?https://t.co/S93CojFVERhttps://t.co/HhkMfAqYdN

— 🛠 Cezary Piatek - Automation Tycoon (@cezary_piatek) December 29, 2020

cc: @spetzu @d_pawlukiewicz @kamgrzybek @oskar_at_net

#microservices

My answer was:

https://twitter.com/oskar_at_net/status/1344184247100329985

The question was short - answer not so much.

Before I answer that let’s start with fundamentals. In distributed environments, we have three main delivery guarantees:

- At-most once - this is the simplest guarantee. You can get it even with in-memory / in-process messaging. When we send a message and processing fails then the message will be lost and not handled. That could happen both for transient and not transient errors. It can be a temporary database outage, losing network the packet, the server is down or not working. The advantage of this is that we do not have to deal with idempotence, but the downside is that we have no guarantee of message delivery.

- At-least once - having this guarantee, we are sure that sent message will always be delivered. However, we are not sure how many times it will be handled. We can achieve that by re-publishing messages on the producer’s side (e.g. with an outbox pattern) or re-handling on the consumer side (e.g. with an inbox pattern). The disadvantage is that the message can be handled several times. We have to defend ourselves through correct idempotency handling. If we don’t do that, we may end up with corrupted data (e.g. we will issue an invoice several times). For example, this can happen when the invoice was saved to the database, but operation timed out. If we retry processing without proper verification if such an invoice already exists, we may duplicate it.

- Exactly-once - this semantic guarantee that sent a message will be handled exactly once. It is very difficult (sometimes even impossible) to achieve, as processing may fail on the multiple stages. If we want to have such guarantee then besides the retries we need to have correct idempotency support. We need to make sure that operation performed several times won’t cause side effects.

Let’s try to explain the funky word “Idempotency”. When the operation is idempotent, it will leave the system in the same state no matter how many times it was performed. If we call it multiple times - the result will be the same. We can achieve that, for example, by sending a unique message identifier. Based on that, we can perform deduplication. If our storage allows transactions, we can store the processed message ids and put a unique constraint on them. If we perform the database change in the same transaction as storing message id then our database will make sure that our operation is idempotent. See more in EventStoreDB idempotency documentation.

The downside is that we always have to perform the check and store an additional record. Plus our storage has to support transactions. Such logic may also have performance degradation.

The other option is verification by the business logic (e.g. checking whether an invoice for a given reservation has already issued).

We should also check if we need more sophisticated idempotency handling. If we’re doing only update or upserts then they’re idempotent by design.

To properly handle at-least-once and exactly-once delivery, following patterns should be used:

-

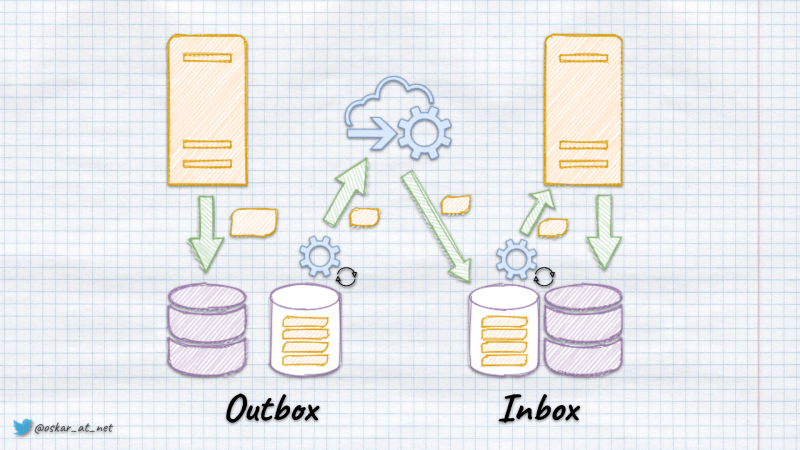

Outbox Pattern - it ensures that a message was sent (e.g. to a queue) successfully at least once. With this pattern, instead of directly publishing a message to the queue, we store it in temporary storage (e.g. database table). We’re wrapping the entity save and message storing with the Unit of Work (transaction). By that, we’re ensuring that the message won’t be lost if the application data is stored. It will be published later through a background process. This process will check if there are any unsent messages in the table. When the worker finds any, it tries to send them. After it gets confirmation of publishing (e.g. ACK from the queue), it marks the event as sent.

Why does it provide at-least-once and not exactly-once? Writing to the database may fail (e.g. it will not respond). When that happens, the process handling outbox pattern will try to resend the event after some time and try to do it until the message is correctly marked as sent in the database.

-

Inbox Pattern - it is similar to Outbox Pattern. It’s used to handle incoming messages (e.g. from a queue). Accordingly, we have a table in which we’re storing incoming events. Contrary to outbox pattern, we first save the event in the database, then we’re returning ACK to queue. If save succeeded, but we didn’t return ACK to queue, then delivery will be retried. That’s why we have at-least-once delivery again. After that, an outbox-like process runs. It calls message handlers that perform business logic.

You can simplify the implementation by calling handlers immediately and sending ACK to the queue when they succeeded. The benefit of using additional table is ability to quickly accept events from the bus. Then they’re processed internally at a convenient pace minimising the impact of transient errors.

Both Outbox and Inbox can be implemented with polling or triggered by the change detection capture.

For polling implementation details you can check a detailed post by Kamil Grzybek.

TLDR. You store events in such table:

CREATE TABLE app.OutboxMessages

(

[Id] UNIQUEIDENTIFIER NOT NULL,

[OccurredOn] DATETIME2 NOT NULL,

[Type] VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL,

[Data] VARCHAR(MAX) NOT NULL,

[ProcessedDate] DATETIME2 NULL,

CONSTRAINT [PK_app_OutboxMessages_Id] PRIMARY KEY ([Id] ASC)

}Then (as described above) you’re processing events in the order of occurrence. After you processed them, you update their ProcessedDate.

That’s a decent option for the regular solution. Sometimes we have higher throughput needs. To allow load balancing and processing in parallel or by multiple outbox consumers it could be updated to e.g.

CREATE TABLE app.OutboxMessages

(

[Id] UNIQUEIDENTIFIER NOT NULL,

[OccurredOn] DATETIME2 NOT NULL,

[Type] VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL,

[Data] VARCHAR(MAX) NOT NULL,

[EventNumber] int NOT NULL AUTO_INCREMENT,

[PartitionKey] VARCHAR(255) NULL,

CONSTRAINT [PK_app_OutboxMessages_Id] PRIMARY KEY ([Id] ASC)

}and adding table:

CREATE TABLE app.OutboxConsumers

(

[Id] UNIQUEIDENTIFIER NOT NULL,

[LastProcessedEventNumber] int,

[PartitionKey] VARCHAR(255) NULL

CONSTRAINT [PK_app_OutboxMessages_Id] PRIMARY KEY ([Id] ASC)

}This change makes possible parallelisation. We no longer update the event after processing. We’re updating the single row in the Outbox Consumers with the last processed event number. Thanks for that:

- We’re getting performance optimisation, as it’s faster to update single row than multiple (e.g. doing batching in outbox),

- It allows for easier locking and implementing competing consumers. See also post by Jeremy D. Miller.

- We can introduce partitioning or sharding and have separate consumers for different partitions. Each consumer will have its entry in OutboxConsumers table differing by PartitionKey. The partition can be, e.g. events stream from single aggregate, events from the module, etc. What’s important to note is that we get the guarantee of ordering for the events within the same partition - so it’s better to consider strategy carefully. See also Marten tenancy documentation.

- Have more than a single consumer (e.g. one for webhooks, one for the queue, etc.)

Change detection capture-based (or also called transactional) takes that on a different level. Polling will always have redundancy, as the background workers need to call database for new events continuously. Almost all popular databases provide functionality for getting triggers when data was changed, e.g.

- Postgres WAL, Npgsql WAL support,

- MSSQL transaction log,

- DynamoDB change streams,

- Change feed in Azure Cosmos DB,

- EventStoreDB subscriptions.

We could use such triggers for outbox processing. Instead of the background process, we get notifications on new events. We can also parallelise processing with routing to different handlers by partition key.

I described that in more details in Push-based Outbox Pattern with Postgres logical replication.

To sum up. Outbox and Inbox patterns are must-haves for getting at-least once or exactly-once delivery. They’re used internally in many solutions like

If you’d like to make your message delivery predictable and successful - you should consider applying that to your system.

I hope that this post helped you! As always - comments are more than welcome! If you’d like to continue investigation around distributed processing, also read my article “Saga and Process Manager - distributed processes in practice”.

Oskar

p.s. I’m thinking about writing library focused on Outbox and Inbox pattern. Please add your comment if you’ll be interested