Structural Typing in TypeScript

When we talk about typing in programming languages, we usually divide it into static and dynamic. Static typing is checked at the compile-time, e.g. in Java, C#, C++. Dynamic typing is checked when the code is run, e.g. in Python or JavaScript.

Both types of typing have their advantages and disadvantages.

Dynamic typing allows you to write more concise code. We can make any transformations as long as their effect works as expected at the end. This allows simplifying the code and cut ceremony but requires more knowledge (or luck) if you want to do it well. You can obviously help yourself using static code analysis (all kinds of linters, analyzers, etc.). The must-have is also a decent set of tests.

Static typing allows you to recognize basic errors at the compile-time, e.g. incorrect type assignment, lack of required fields, or even a stupid typo in the field name. It’s easier to do refactoring because we can immediately see if we broke something. It also easier to manage quality in teams with various levels of experience. In theory, types and compilation will save us from stupid mistakes. However, we also often have to flex ourselves to please the type system. Often, more code needs to be generated. There is always something for something.

Here we get to the subject of this article. What is structural typing?

Static typing can be divided into nominal and structural.

In nominal typing, when assessing whether a given object is of a specific type, we verify:

- type name,

- fields’ presence,

- fields’ names,

- fields’ types.

Structural typing do not care about the type name. It checks whether the object’s structure agrees with the pattern restrained by type definition (fields’ presence, names and types). We take the type template and try to fit the object in it. If we manage to do that, then the object is of a given type. It can also be compared to the definition of a human being. A human is a mammal; it has legs, arms and head. However, if the definition is too general, a monkey can also be considered a human. After all, it is also a mammal; it has legs, arms and head.

Look below:

interface Human {

legs: number,

hands: number

}

interface Employee {

legs: number,

hands: number,

name: string

}

const johnDoe = {

legs: 2,

hands: 2,

name: "John Doe"

}

const ape = {

legs: 2,

hands: 2

}

const snake = {

tounge: true,

}

// OK

let human: Human = johnDoe;

let employee: Employee = johnDoe;

// OK

human = ape;

// Fail - missing name

employee = ape;

// Fail - missing legs, hands

human = snake;

// Fail - missing egs, hands, name

employee = snake;As you can see, variables definitions do not have any type name. Typescript compiler does not need that. It only checks if the object structure matches the type definition. It may look strange at first, but it offers a lot of possibilities. If, for example, we have a function to display the name, we do not have to create an additional interface and have each class implementing it. We can just do this:

function printName(name: { firstName:string, lastName: string }) {

console.log(`${name.firstName} ${name.lastName}`);

}This allows for a lot of ceremonies, especially if we write in a more functional style.

Like everything, it has its advantages and disadvantages. A lot of people who come from the world of _ “nominal typing” _ (read C#, Java) don’t try to understand that TypeScript is a language of a different (nomen omen) type. They try to forcefully transfer their preferences and cram interfaces and classes everywhere. They limit the room for manoeuvre and reduce the programming environment to the lowest common denominator.

Never mind if it is just dragging ballast. That might be someone’s preference. The problem starts when one forgets that TypeScript is not a compiled language - it is a transpiled language. TypeScript doesn’t enforce types at runtime. It just validates them and translates them to JavaScript code. Once this is done and you run your code, it is already dynamically typed JavaScript. Paper approves of anything, and so will JavaScript.

The worst thing we can do is handle the request like this:

function addEmployee(user: Employee) {

if (!user?.name && user?.legs !== 2 && !user?.hands !== 2) {

throw "Not an Employee";

}

saveToDatabase(user);

}Why is it so bad? We have validation. Everything looks correct. Well no. In fact, underneath (especially after deserialization), our object may have additional fields, the structure may be extended - e.g. someone can send:

{

"name": {

"firstName": "John",

"lastName": "Doe"

},

"legs": 2,

"hands": 2,

"iWillSpamYourDB": "someExtremelyLargeText(...)"

}And if we’ll just deserialize and assume that we know what the type is, we’ll be shocked. Therefore, the first thing I suggest doing is rewrite the fields and create a new object after validation. We can trust the objects in our code (let’s say), never the external ones.

function addEmployee(userRequest: any) {

if (!userRequest?.name && userRequest?.legs !== 2 && !userRequest?.hands !== 2) {

throw "Not an Employee";

}

const user: User = {

name: userRequest.name,

legs: userRequest.legs,

hands: userRequest.hands

}

saveToDatabase(user);

}This may seem redundant, but it gives us confidence in our code and types plus protects us from unsafe behaviour.

Personally, I think structural typing is excellent. It simplifies our life and gives us superb opportunities.

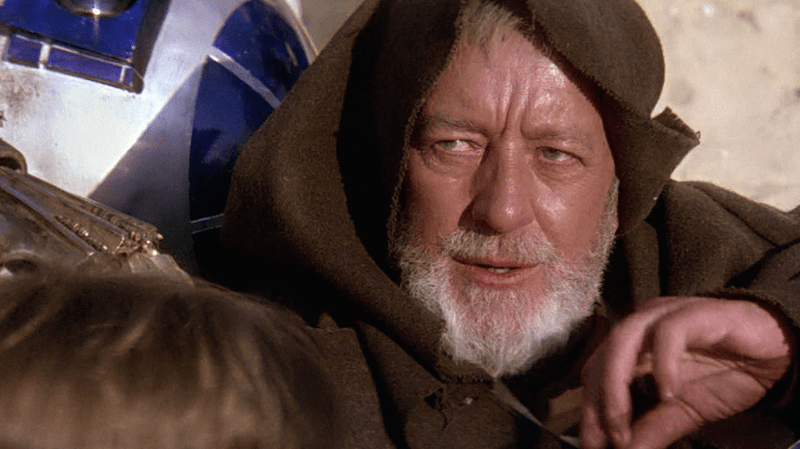

When we start working in a new environment, let’s tackle it open-minded We should not take the easy way and do not try to blindly transfer our habits, but understand the conventions and differences. Because it may turn out that these are not the droids we’re looking for.

Cheers!

Oskar

p.s. Check also my post about why partial types are neat in TypeScript.