Straightforward Event Sourcing with TypeScript and NodeJS

In the last two articles, I explained how to organise your business logic effectively, showing how proper typing and composition can help to achieve that. That came with an explanation of the Decider pattern and a few other like Either and Maybe data structures. The samples used Object-Oriented languages, so Java and C#. That was intentional, as I wanted to show that if you could make it there, you could make it anywhere.

Today, I’d like to wrap up the series and show how this could look in the language with native support for union types. I decided to use TypeScript. Yup I was also a hater of it some time ago, but now I think it’s a cool language that, together with NodeJS, makes development quick and cuts the amount of boilerplate compared to other environments.

If you didn’t read previous articles, let’s do a recap:

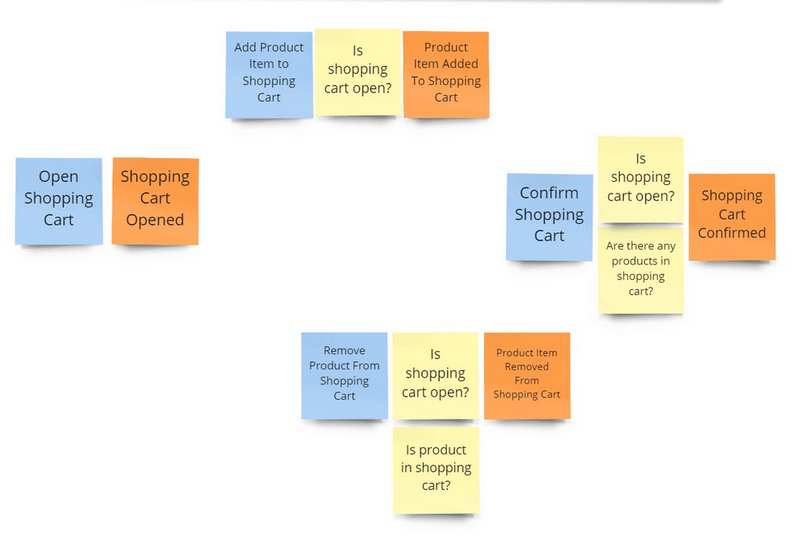

- we’re modelling the shopping cart process. You can open it, add or remove the product from it and confirm or cancel.

- we want to have a little help from our friends: types. They should reflect all the possible states. We want compiler checks to prevent dummy mistakes and reduce the number of unit tests.

- All of that will allow us to express our business logic in our code better. It’ll also give us better trust in our code.

The logic looks like this:

Ah, I forgot, I’m using Event Sourcing in the examples, because why not? It’s cool, but if you don’t want to do it, all those composition patterns and strategies also apply to the traditional approach.

Let’s start with the event definition:

export type ShoppingCartEvent =

| {

type: 'ShoppingCartOpened';

data: {

shoppingCartId: string;

clientId: string;

openedAt: string;

};

}

| {

type: 'ProductItemAddedToShoppingCart';

data: {

shoppingCartId: string;

productItem: ProductItem;

};

}

| {

type: 'ProductItemRemovedFromShoppingCart';

data: {

shoppingCartId: string;

productItem: ProductItem;

};

}

| {

type: 'ShoppingCartConfirmed';

data: {

shoppingCartId: string;

confirmedAt: string;

};

}

| {

type: 'ShoppingCartCanceled';

data: {

shoppingCartId: string;

canceledAt: string;

};

};We’re defining ShoppingCartEvent type as a union of other types. It means that it’ll be either one or another. As underneath TypeScript, once we compile it, there is a good Ye Olde JavaScript we need to somehow be able to find the difference between our objects to know the type. To do that, we’re using the type field. Thanks to that, each type will have its own unique type name that will differentiate it from others. If you’re afraid of stringly typing, don’t worry, you’ll get all IntelliSense and compiler checks guarding you against any stupid mistakes.

The field discriminating our union type doesn’t have to be named type. In fact, we can use any field for that. For instance, we could name it status and use it like that:

export type ShoppingCart =

| {

status: 'Empty';

}

| {

status: 'Pending';

id: string;

clientId: string;

productItems: ProductItem[];

}

| {

status: 'Confirmed';

id: string;

clientId: string;

productItems: ProductItem[];

confirmedAt: Date;

}

| {

status: 'Canceled';

id: string;

clientId: string;

productItems: ProductItem[];

canceledAt: Date;

};This is our shopping cart states definition. As this is a simple state machine, the status is unique for each state.

Now, to show you that, we could also use that for more advanced stuff, like pattern matching. Let’s see how we could build the current state from a list of events. I described this pattern in my other articles:

- Why Partial

is an extremely useful TypeScript feature? - How to get the current entity state from events?

In short, we’re taking a sequence of events, the default object and applying them gradually. For that, we need the function that will return the new state from the current one and an event. This function is usually called when, apply or evolve and can look like that:

export const evolve = (

currentState: ShoppingCart,

event: ShoppingCartEvent

): ShoppingCart => {

switch (event.type) {

case 'ShoppingCartOpened':

if (currentState.status != 'Empty') return currentState;

return {

id: event.data.shoppingCartId,

clientId: event.data.clientId,

productItems: [],

status: 'Pending',

};

case 'ProductItemAddedToShoppingCart':

if (currentState.status != 'Pending') return currentState;

return {

...currentState,

productItems: addProductItem(

currentState.productItems,

event.data.productItem

),

};

case 'ProductItemRemovedFromShoppingCart':

if (currentState.status != 'Pending') return currentState;

return {

...currentState,

productItems: removeProductItem(

currentState.productItems,

event.data.productItem

),

};

case 'ShoppingCartConfirmed':

if (currentState.status != 'Pending') return currentState;

return {

...currentState,

status: 'Confirmed',

confirmedAt: new Date(event.data.confirmedAt),

};

case 'ShoppingCartCanceled':

if (currentState.status != 'Pending') return currentState;

return {

...currentState,

status: 'Canceled',

canceledAt: new Date(event.data.canceledAt),

};

default: {

const _: never = event;

return currentState;

}

}

};As you can see, I’m using pattern matching here based on the event type and returning the new state. To get the final state, we need to call:

const events = await readStream<ShoppingCartEvent>(eventStore, streamId);

const shoppingCart = events.reduce<ShoppingCart>(

evolve,

{ status: 'Empty' }

);Getting the current state is the first step to being able to run the business logic. Event Sourcing is no different in that. Let’s define the set of operations that we could do for our shopping cart. Again we’ll use the union type definition.

export type ShoppingCartCommand =

| {

type: 'OpenShoppingCart';

data: {

shoppingCartId: string;

clientId: string;

};

}

| {

type: 'AddProductItemToShoppingCart';

data: {

shoppingCartId: string;

productItem: ProductItem;

};

}

| {

type: 'RemoveProductItemFromShoppingCart';

data: {

shoppingCartId: string;

productItem: ProductItem;

};

}

| {

type: 'ConfirmShoppingCart';

data: {

shoppingCartId: string;

};

}

| {

type: 'CancelShoppingCart';

data: {

shoppingCartId: string;

};

};What would you say for a bit of business logic? Yeah, let’s go; that’s what we’re here for. As our Shopping Cart is not the most sophisticated one, we’ll use some pattern-matching magic again.

const decide = (

{ type, data: command }: ShoppingCartCommand,

shoppingCart: ShoppingCart

): ShoppingCartEvent | ShoppingCartEvent[] => {

switch (type) {

case 'OpenShoppingCart': {

if (shoppingCart.status != 'Empty') {

throw ShoppingCartErrors.CART_ALREADY_EXISTS;

}

return {

type: 'ShoppingCartOpened',

data: {

shoppingCartId: command.shoppingCartId,

clientId: command.clientId,

openedAt: new Date().toJSON(),

},

};

}

case 'AddProductItemToShoppingCart': {

if (shoppingCart.status !== 'Pending') {

throw ShoppingCartErrors.CART_IS_ALREADY_CLOSED;

}

return {

type: 'ProductItemAddedToShoppingCart',

data: {

shoppingCartId: command.shoppingCartId,

productItem: command.productItem,

},

};

}

case 'RemoveProductItemFromShoppingCart': {

if (shoppingCart.status !== 'Pending') {

throw ShoppingCartErrors.CART_IS_ALREADY_CLOSED;

}

assertProductItemExists(shoppingCart.productItems, command.productItem);

return {

type: 'ProductItemRemovedFromShoppingCart',

data: {

shoppingCartId: command.shoppingCartId,

productItem: command.productItem,

},

};

}

case 'ConfirmShoppingCart': {

if (shoppingCart.status !== 'Pending') {

throw ShoppingCartErrors.CART_IS_ALREADY_CLOSED;

}

return {

type: 'ShoppingCartConfirmed',

data: {

shoppingCartId: command.shoppingCartId,

confirmedAt: new Date().toJSON(),

},

};

}

case 'CancelShoppingCart': {

if (shoppingCart.status !== 'Pending') {

throw ShoppingCartErrors.CART_IS_ALREADY_CLOSED;

}

return {

type: 'ShoppingCartCanceled',

data: {

shoppingCartId: command.shoppingCartId,

canceledAt: new Date().toJSON(),

},

};

}

default: {

const _: never = command;

throw ShoppingCartErrors.UNKNOWN_COMMAND_TYPE;

}

}

};Based on the type of command, we’re running certain business logic. And as a result, returning the new event represents the recorded business fact.

“That’s naive! What if we have real business logic?!” - you could say. My answer is that composition is the king. If you carefully check the code snippets, you may notice that I already cheated on you. I skipped some of the helper functions for product items. Here they are:

export interface ProductItem {

productId: string;

quantity: number;

}

export const addProductItem = (

productItems: ProductItem[],

newProductItem: ProductItem

): ProductItem[] => {

const { productId, quantity } = newProductItem;

const currentProductItem = findProductItem(productItems, productId);

if (!currentProductItem) return [...productItems, newProductItem];

const newQuantity = currentProductItem.quantity + quantity;

const mergedProductItem = { productId, quantity: newQuantity };

return productItems.map((pi) =>

pi.productId === productId ? mergedProductItem : pi

);

};

export const removeProductItem = (

productItems: ProductItem[],

newProductItem: ProductItem

): ProductItem[] => {

const { productId, quantity } = newProductItem;

const currentProductItem = assertProductItemExists(

productItems,

newProductItem

);

const newQuantity = currentProductItem.quantity - quantity;

if (newQuantity === 0)

return productItems.filter((pi) => pi.productId !== productId);

const mergedProductItem = { productId, quantity: newQuantity };

return productItems.map((pi) =>

pi.productId === productId ? mergedProductItem : pi

);

};

export const findProductItem = (

productItems: ProductItem[],

productId: string

): ProductItem | undefined => {

return productItems.find((pi) => pi.productId === productId);

};

export const assertProductItemExists = (

productItems: ProductItem[],

{ productId, quantity }: ProductItem

): ProductItem => {

const current = findProductItem(productItems, productId);

if (!current || current.quantity < quantity) {

throw ShoppingCartErrors.PRODUCT_ITEM_NOT_FOUND;

}

return current;

};As you can see, by the proper composition of small functions and types, we can reduce the cognitive load, so the amount of knowledge we need to adhere to at once.

We could also generalise our processing logic and define the following types:

export type Event<

EventType extends string = string,

EventData extends Record<string, unknown> = Record<string, unknown>

> = {

type: EventType;

data: EventData;

};

export type Command<

CommandType extends string = string,

CommandData extends Record<string, unknown> = Record<string, unknown>

> = {

type: CommandType;

data: CommandData;

};

export type Decider<

State,

CommandType extends Command,

EventType extends Event

> = {

decide: (command: CommandType, state: State) => EventType | EventType[];

evolve: (currentState: State, event: EventType) => State;

getInitialState: () => State;

};At first glance, this may look a bit cryptic. Yet it just tells that event is an object that has:

- type property, that’s string

- data property that’s a record, so a complex object.

The same goes for commands.

Having that, we can define a Decider. It’s a pattern defined by Jérémie Chassaing that shows how to organise our business logic in the event-driven world. It takes the following functions:

- decide, that runs the command’s business logic on the current state returning event or sequence of events as a result,

- evolve, that applies the event on the state,

- getInitialState, which returns the default, not initialised state.

We already defined everything, so let’s group it into a specific function:

export const decider: Decider<

ShoppingCart,

ShoppingCartCommand,

ShoppingCartEvent

> = {

decide,

evolve,

getInitialState: () => {

return {

status: 'Empty',

};

},

};We could call it a day and finish now. Most of the composition techniques were discussed, but we won’t! Let’s try to go further and code the fully working Web API using those patterns.

Let’s start with the definition of the command handler. We’ll use Optimistic Concurrency with ETag to guarantee that we’re making decisions based on the latest state.

export const CommandHandler =

<State, CommandType extends Command, EventType extends Event>(

getEventStore: () => EventStoreDBClient,

toStreamId: (recordId: string) => string,

decider: Decider<State, CommandType, EventType>

) =>

async (

recordId: string,

command: Command,

eTag: ETag | undefined = undefined

): Promise<AppendResult> => {

const eventStore = getEventStore();

const streamId = toStreamId(recordId);

const events = await readStream<EventType>(eventStore, streamId);

const state = events.reduce<State>(

decider.evolve,

decider.getInitialState()

);

const newEvents = decider.decide(command, state);

const toAppend = Array.isArray(newEvents) ? newEvents : [newEvents];

return appendToStream(eventStore, streamId, eTag, ...toAppend);

};Command handler is a wrapper function that takes event store client factory and decider and records id to stream id mapper. It returns the handler function that takes the record id, command and ETag. It:

- reads the stream events,

- based on them, builds the current state using the decider’s evolve function,

- then, it runs decide function that returns event(s) as a result,

- those events are appended back to the stream.

Btw. this wrapping technique is called currying.

Implementation with EventStoreDB could look like this:

let eventStore: EventStoreDBClient;

export const getEventStore = (connectionString?: string) => {

if (!eventStore) {

eventStore = EventStoreDBClient.connectionString(

connectionString ?? 'esdb://localhost:2113?tls=false'

);

}

return eventStore;

};

export const readStream = async <EventType extends Event>(

eventStore: EventStoreDBClient,

streamId: string

) => {

const events = [];

for await (const { event } of eventStore.readStream<EventType>(streamId)) {

if (!event) continue;

events.push(<EventType>{

type: event.type,

data: event.data,

});

}

return events;

};

export type AppendResult =

| {

nextExpectedRevision: ETag;

successful: true;

}

| { expected: ETag; actual: ETag; successful: false };

export const appendToStream = async (

eventStore: EventStoreDBClient,

streamId: string,

eTag: ETag | undefined,

...events: Event[]

): Promise<AppendResult> => {

try {

const result = await eventStore.appendToStream(

streamId,

events.map(jsonEvent),

{

expectedRevision: eTag ? getExpectedRevisionFromETag(eTag) : NO_STREAM,

}

);

return {

successful: true,

nextExpectedRevision: toWeakETag(result.nextExpectedRevision),

};

} catch (error) {

if (error instanceof WrongExpectedVersionError) {

return {

successful: false,

expected: toWeakETag(error.expectedVersion),

actual: toWeakETag(error.actualVersion),

};

}

throw error;

}

};See also ETag helpers for brevity:

export type WeakETag = `W/${string}`;

export type ETag = WeakETag | string;

export const WeakETagRegex = /W\/"(\d+.*)"/;

export const enum ETagErrors {

WRONG_WEAK_ETAG_FORMAT = 'WRONG_WEAK_ETAG_FORMAT',

MISSING_IF_MATCH_HEADER = 'MISSING_IF_MATCH_HEADER',

}

export const isWeakETag = (etag: ETag): etag is WeakETag => {

return WeakETagRegex.test(etag);

};

export const getWeakETagValue = (etag: ETag): string => {

const result = WeakETagRegex.exec(etag);

if (result === null || result.length === 0) {

throw ETagErrors.WRONG_WEAK_ETAG_FORMAT;

}

return result[1];

};

export const toWeakETag = (value: any): WeakETag => {

return `W/"${value}"`;

};

export const getExpectedRevisionFromETag = (eTag: ETag): bigint =>

assertUnsignedBigInt(getWeakETagValue(eTag));We need to go deeper! Or higher. As we have such a nice command handler, let’s try to sprinkle it with HTTP on top of it to be able to handle ExpressJS routing.

export const HTTPHandler =

<Command, RequestType extends Request = Request>(

handleCommand: (

recordId: string,

command: Command,

eTag?: ETag

) => Promise<AppendResult>

) =>

(

mapRequest: (

request: RequestType,

handler: (recordId: string, command: Command) => Promise<void>

) => Promise<void>

) =>

async (request: RequestType, response: Response, next: NextFunction) => {

try {

await mapRequest(request, async (recordId, command) => {

const result = await handleCommand(

recordId,

command,

getETagFromIfMatch(request)

);

return mapToResponse(response, recordId, result);

});

} catch (error) {

next(error);

}

};

export const getETagFromIfMatch = (request: Request): ETag => {

const etag = request.headers['if-match'];

if (etag === undefined) {

throw ETagErrors.MISSING_IF_MATCH_HEADER;

}

return etag;

};

export const mapToResponse = (

response: Response,

recordId: string,

result: AppendResult,

urlPrefix?: string

): void => {

if (!result.successful) {

response.sendStatus(412);

return;

}

response.set('ETag', toWeakETag(result.nextExpectedRevision));

if (result.nextExpectedRevision == toWeakETag(0)) {

sendCreated(response, recordId, urlPrefix);

return;

}

response.status(200);

};

export const sendCreated = (

response: Response,

createdId: string,

urlPrefix?: string

): void => {

response.setHeader(

'Location',

`${urlPrefix ?? response.req.url}/${createdId}`

);

response.status(201).json({ id: createdId });

};Again we’re doing function returning function. Or, to be precise, function returning function returning function. I know how that sounds, but here we go:

- The main one takes the command handler function with the record identifier and command and returns the function.

- The next one takes the HTTP request and has a callback function that we should call to handle the request to command mapping.

- The last one is a classical routing function. It takes a request, gets ETag from it, maps the request to command and calls the handler method from the parameter of the initial function. After that, it does dance around the proper HTTP response status handling. It returns 201 when a new record was created, 412 if there was an optimistic concurrency check failed, and 200 otherwise. It also wraps it with a try/catch block to do proper response disposal.

If that looks too complex, then I hope that merging all of that will make it clearer.

const handleCommand = CommandHandler<

ShoppingCart,

ShoppingCartCommand,

ShoppingCartEvent

>(

getEventStore,

(shoppingCartId: string) => `shopping_cart-${shoppingCartId}`,

decider

);

const on = HTTPHandler<ShoppingCartCommand>(handleCommand);We’re composing at first command handler and using it to build a generic HTTP handler. We can use it to define our endpoints as follows:

export const router = Router();

// Open Shopping cart

router.post(

'/clients/:clientId/shopping-carts/',

on((request, handle) => {

const shoppingCartId = uuid();

return handle(shoppingCartId, {

type: 'OpenShoppingCart',

data: {

shoppingCartId,

clientId: assertNotEmptyString(request.params.clientId),

},

});

})

);

// Add Product Item

router.post(

'/clients/:clientId/shopping-carts/:shoppingCartId/product-items',

on((request, handle) => {

const shoppingCartId = assertNotEmptyString(request.params.shoppingCartId);

return handle(shoppingCartId, {

type: 'AddProductItemToShoppingCart',

data: {

shoppingCartId: assertNotEmptyString(request.params.shoppingCartId),

productItem: {

productId: assertNotEmptyString(request.body.productId),

quantity: assertPositiveNumber(request.body.quantity),

},

},

});

})

);

// Remove Product Item

router.delete(

'/clients/:clientId/shopping-carts/:shoppingCartId/product-items',

on((request, handle) => {

const shoppingCartId = assertNotEmptyString(request.params.shoppingCartId);

return handle(shoppingCartId, {

type: 'RemoveProductItemFromShoppingCart',

data: {

shoppingCartId: assertNotEmptyString(request.params.shoppingCartId),

productItem: {

productId: assertNotEmptyString(request.query.productId),

quantity: assertPositiveNumber(request.query.quantity),

},

},

});

})

);

// Confirm Shopping Cart

router.put(

'/clients/:clientId/shopping-carts/:shoppingCartId',

on((request, handle) => {

const shoppingCartId = assertNotEmptyString(request.params.shoppingCartId);

return handle(shoppingCartId, {

type: 'ConfirmShoppingCart',

data: {

shoppingCartId: assertNotEmptyString(request.params.shoppingCartId),

},

});

})

);

// Confirm Shopping Cart

router.delete(

'/clients/:clientId/shopping-carts/:shoppingCartId',

on((request, handle) => {

const shoppingCartId = assertNotEmptyString(request.params.shoppingCartId);

return handle(shoppingCartId, {

type: 'CancelShoppingCart',

data: {

shoppingCartId: assertNotEmptyString(request.params.shoppingCartId),

},

});

})

);As you can see, all of the routes definition just need to define the mapping logic from the request to command and call the callback. The rest will be handled internally. Thanks to the composition and type definition, we’re still getting compiler checks and are guarded by that.

See, besides going a bit wild with command handling definition, we just used simple types and specific types definitions. That helped us to reflect the business process in our code and keep our logic short and concise. TypeScript gave us a more succinct and less verbose code definition. NodeJS, cutting the boilerplate of the WebApi frameworks.

I encourage you to play with that and get your own opinion. Source codes are available here: https://github.com/oskardudycz/EventSourcing.NodeJS/pull/21.

This approach can be also helpful to classical state-based approach. Read more in How events can help in making the state-based approach efficient.

Cheers!

Oskar

p.s. Ukraine is still under brutal Russian invasion. A lot of Ukrainian people are hurt, without shelter and need help. You can help in various ways, for instance, directly helping refugees, spreading awareness, putting pressure on your local government or companies. You can also support Ukraine by donating e.g. to Red Cross, Ukraine humanitarian organisation or donate Ambulances for Ukraine.