What's the difference between a command and an event?

What’s the difference between a command and an event?

The answer seems apparent, but let’s see if it’s straightforward.

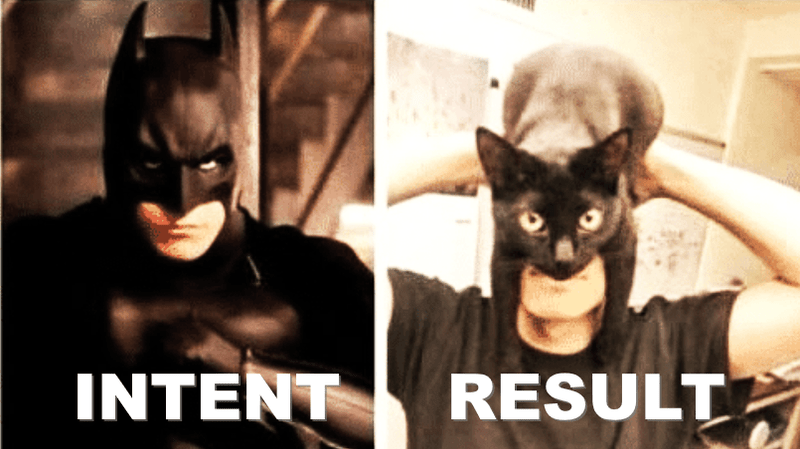

The command represents the intention. It targets a specific audience. It can be your friend when you’re asking “pass me the salt”. It can be an application service and request with intention to “add user” or “change the order status to confirmed”. So the sender of the command must know the recipient and expects the request to be executed. Of course, the recipient may refuse to do it by not passing us the salt or throwing an exception during the request handling.

The event, in turn, represents a fact in the past. It carries information about something accomplished. What has been seen, cannot be unseen. Following our examples “user added”, “order status changed to confirmed” are facts in the past. We do not direct events to a specific recipient, we broadcast the information. It’s like telling a story at a party. We hope that someone listens to us, but we may quickly realise that no one is paying attention.

What the event and the command have in common?

Both are messages. They convey specific information; a command about the intent to do something, or an event about the fact that happened. From the computer’s point of view, they are no different. Only the business logic and the interpretation of the message can find the difference between event and command.

Commands are usually assumed to be synchronous and events to be asynchronous. We typically send commands via, e.g. Rest API, events via queues (In-memory, RabbitMQ, Kafka etc.). This distinction comes from custom. When we’re sending a command, we’d like to know immediately whether it has been done or not. Usually, we want to do an alternative scenario or error handling when the operation failed. Likewise, we typically assume that it is better to immediately stop the process, e.g. buying a cinema ticket than wait and refresh and see if it has worked.

It makes sense, but it’s not always so obvious. For example, a bank transfer: when we make it, it won’t happen right away. We have to wait for a while. It’s the same when making a purchase on the Internet. Placing an order and making a payment doesn’t immediately finish the whole process. It still has to be shipped, the invoice issued, etc. This is an asynchronous process, so the results of our commands may also be asynchronous.

Microservices and distributed systems add additional complexity.

Traditionally, the sender needed to know who to tell to take over the rest of the work. Using queuing/streaming systems reverse the services’ dependency. The sender publishes the message to the unified channel, the recipient subscribes and waits for it. When we buy a cinema ticket, a receipt must be generated, the seat must be reserved, the user should be notified by e-mail and displayed on the website. All that can be split into separate workflow steps. Which one should be triggered by a command and which one by the event?

We could use heuristics: we send the command when the recipient has the right to refuse the request and event when the recipient just accepts it. If we want to add a user, the system may refuse when we used the existing username. Can a financial service refuse the reservation service to generate a receipt? If the reservation is confirmed, transfer was made, then the financial module should just accept it. So, is it an event?

In theory, yes, if there are no validation rules and if the event happened then, the other system should accept it and perform the logic. Kafka-like streaming systems should guarantee delivery even if the financial service is temporarily unavailable. We have bugs in the code? Then we have to fix them.

Here, the theory ends, and practice begins. Our customer doesn’t care if the error is a bug that we know and fix it in the near future? The customer wants to do a business and be operational.

Of course, in the message queuing tutorials, you can find suggestions like: “There is a dead-letter queue/poison-message queue where not-processed messages will be put. You can check there and react”. That’s cool, but how many people are monitoring it? And even if they do, how quickly will they be able to react? Let’s assume that we collect metrics, send alerts, support responses quickly, and report a ‘ticket’ to programmers. How quickly will they fix it? We can ease that with the design upfront and adding the compensating operation (e.g. button in the UI to generate the invoice if the reservation confirmed event was lost).

Sometimes it turns out that a given event will always have only one recipient. What’s more, we expect it to be always handled. Is it still an event? It is worth considering whether we’re not sending the command “issue a receipt” under the event with the “reservation was confirmed” name. When the business process is crucial, we may prefer to fail fast and have an immediate result. For such cases, it’s worth considering whether it would be better to do an asynchronous command instead of an asynchronous event.

Of course, we’re touching here on the separate topic of the distributed processes. By itself it’s non-trivial. You can read more on that in my other posts:

- “Saga and Process Manager - distributed processes in practice”

- “Outbox, Inbox patterns and delivery guarantees explained”

The distinction between commands and events may not be so simple as it looks. We need to take many factors into consideration:

- Is it an intention to do something or the recorded fact?

- Is it asynchronous or synchronous operation?

- Can it have multiple recipients?

- Is it business-critical?

- And many more

If someone asks you “is it a command or an event”, don’t be afraid to say “it depends” and start to work on the business logic understanding.

Oskar