How to design software architecture pragmatically

I’ve run numerous workshops in recent years. It’s intriguing to see different ways people solve the same problem. Some start from general vision and go into details, some the other way.

Some focus on making the design look nice and tidy on the drawing board and strictly following design methodology. Others do not care about the form and rules of the tool used and just let it fly.

Each approach has advantages and disadvantages. I want to share some conclusions based on my practice and how I work with modelling, design, etc.

The first stage of working with a completely new functionality is the creative stage. We don’t know much about the problem and tooling stack. We find dots and connect them. A suitable method here is good old brainstorming.

Here are a few rules for making it effective:

- there are no stupid ideas,

- we don’t criticize; we focus on our ideas, not other people’s,

- we generate as many ideas as possible,

- when we run out of ideas, we should still try to grind a bit longer and tell ourselves to generate 2-3 more. It’s like running; often, the best results occur when we pass the first fatigue threshold,

- however, it is important to set a maximum duration for brainstorming. It should be an intensive and productive meeting. There’s no point in making it an endless one. You can always organize several sessions.

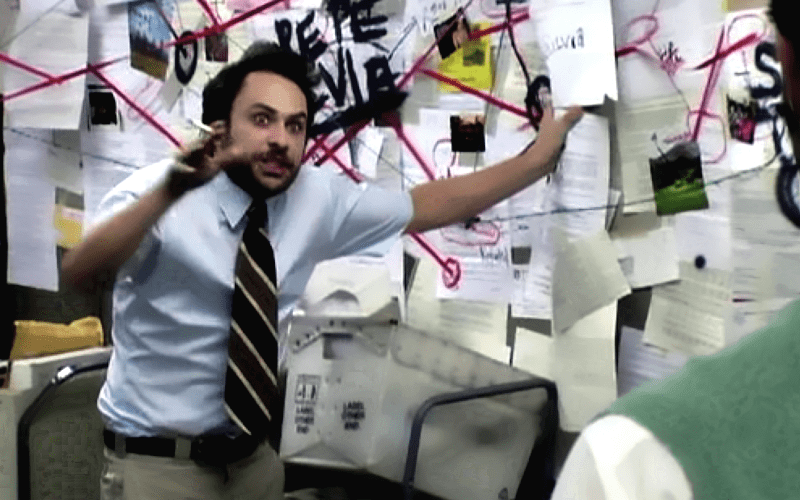

That is why tools such as EventStorming and other sticky-notes-based tools are so popular. They allow us to throw our ideas onto the wall, crunch them and stimulate discussions.

Having a good mixture of people at such a meeting is essential. We should have people of all sorts: programmers, business people and testers. We’re discussing the general vision at the early stages here, so every perspective counts.

Yet, it’s also essential to not have too many people and care for mental health. Doing continuous brainstorming sessions can be draining and ineffective. We need to let our thoughts sink in. I’m personally an introvert, and I’m emotionally exhausted after a set of longer sessions and need time to recover (read more in Agile vs Introverts).

Thus, after brainstorming, it is worth sifting out what we have found. We should group ideas by category. Even if some look like duplicates, discussing them before we throw them out is crucial. Often, such details contain grey matter, so details that can have a significant impact but are easy to miss.

The brainstorming itself may concern specific functionalities as well as the global vision of the system. EventStorming divides this into “big picture” and “process/design level”. First, we look at the events that are essential from the overall system perspective, then we go lower (read more about the distinction between internal and external events on my blog: “Events should be as small as possible, right?”).

Although the “big picture” indicates that in EventStorming, we move from general to specific, we also go the other way round. The starting point is finding events; they are granular and precise by definition. We’re shaping the business workflow by grouping and placing them in order. We can also find boundaries, language nuances and define bounded contexts. Having that, we can go down the rabbit hole again, breaking down processes into smaller functionalities.

Another technique that helps you move from general to specific is the good old Mind Map. Starting from the main block, which may represent, for example, our system, we can break it down into details - e.g. answering the question “what do I need to have to build this system?”. Having general answers and overall ideas, we can ask similar questions on those answers and find more details.

Such an approach has a name: “5 whys” method. We can ask the business more questions, why, to find out the actual source of the problem. I detailed that in Bring me problems, not solutions!.

Those tools are great but often difficult to translate directly into implementation. I had many cases when people finished their brainstorming sessions, having distilled their current process and were super proud of what they did. Unfortunately, I broke the charm by asking them: “ok, what’s next?”. Usually, the answer was surprised the isn’t-that-already-the-end? look.

Nope, it’s not the end. The result of brainstorming is just an entry point for the proper system design. As I outlined in the other article, the design flow should look like this:

- WHAT? Describe and model the business workflow. Understand the product requirements and follow the money to find why they’re important from the business perspective.

- HOW? Think about the requirements and guarantees you need to have. Find architecture patterns and class of solutions that will fulfil your requirements. So, the type of databases, deployment type, integration patterns, not the specific technologies.

- WITH. Select the tooling based on the outcome of the previous point. It has to fulfil requirements, but also non-functional like costs, match team experience, ease of use, etc.

Brainstorming is at the WHAT level. We still need to understand HOW and WITH.

What design tools can help us to move further?

An interesting one is the C4 model. which allows us to zoom in and out perspective on our system. We have four contexts:

- System: all the internal and external systems involved in our solution.

- Containers: all of our deployment units, so everything we need to take care of, deploy, monitor etc. That includes both services and tools like messaging tooling, databases, etc.

- Components: now we look deeper and see the components of the specific deployment units. We can see modules here and the logical split of the bigger building blocks.

- Code - all the code structures, implementation patterns, communication between them, etc.

We start with a general vision of the system and go lower and lower. Thanks to this, by dividing our architecture into individual levels, we create diagrams that are clear in a given context and allow us to understand what our system does and see how. Read also more on what factors to take into account in How (not) to cut microservices.

I typically prefer a general-to-detail approach, but I also always drill test boreholes. By that, I’m setting tunnel vision on key functionalities, verifying the hypothesis, and ensuring what we thought would work in practice. It is an excellent place for prototyping, an underestimated design skill. You can do both purely technical spike and implementing business models. We can confront both technical and business assumptions.

Running such spikes is essential because if we do not do it, we risk that some functionality will become a dead end, and the overall design will have to be changed because of it.

Are you afraid to code? there’s another tool you can use, right on paper: Risk Register. I explained it in The risk of ignoring risks. The risk register is a simple table. We write down all risks for our solution. We write the probability in the lines and the degree of risk in the columns. By multiplying these two data, we get a result that tells us how much we should focus on a given risk. If we find out that our risks are very probable and the consequences of their occurrence are severe, then it’s better to change our way. If the risk is unlikely with little consequence, we can ignore it. Usually, however, it is somewhere in the middle. We should write down what we will do when the risk occurs. Thanks to that, we can find the threats more easily and define strategies to deal with them or change design to make it more resilient. We should not be afraid to make decisions, this is the tool that can help us with that.

Other useful, low-level tools are UML Sequence and Activity diagrams. They allow you to describe a specific flow in more detail. Keeping them as small and focused as possible is critical to keep them readable. You can always make several for the same functionality, showing different variants (e.g. happy path, error flow, etc.).

Of course, I described only sample tools above; there are plenty of them. Perhaps too much. They have become surrounded by consultants who make the business by teaching them. When reading some materials, you could think that using a modelling methodology and creating a design is enough, and the code will write itself. That’s obviously not the case.

Common sense and adapting the tools to my needs are important for me. I sometimes do sketches on paper instead of specific methodologies. I like to create blocks in an application like draw.io. They may not be the most maintainable in the long term, but they can provide a good entry point for discussion or immutable decision record.

Maintainability of the outcome of design artefacts is also an essential aspect of those methodologies. Some are better for discussion, and some are static documentation. Brainstorming tools are rarely maintainable; they’re designed to trigger discussions and creativity, which often is chaotic. You will probably not be able to keep the EventStorming model in Miro up to date, but you should be able to do that with the C4 model (especially with levels 1-3; 4th could be generated from code).

For group discussions and brainstorming, I recommend using ready-made methods with specific notations (e.g., EventStorming, C4). They eliminate discussions on what notation we’ll use, what’s this or that. It helps to focus on the merit, so design discussions instead of trying to understand what this box means for other people.

Of course, we are not always able to arrange group sessions. Not every organisation allows to do that on a regular basis. However, we should still do it. We can always do design sessions within the team; if our team is unwilling, we can start with ourselves. We should not stop ourselves from visualising, writing down and prototyping our design. It is part of our job and responsibility as engineers. If it helps us, we can show the result to others. It will be easier to convince others to do so once they see it working.

What if you don’t know how to do it? Just try it. The first times are usually clumsy. The ability to model a system is a skill like any other. It requires repetition and practice. It will get easier with each subsequent attempt.

It’s also easier now. Many tools support these days collaborative design and popular methodologies. They make it easier to catalyze discussions between teams.

You can also make a dry run with your teams doing Architecture Katas as a form of team-building exercise.

The best time to start is not tomorrow but now.

How do you approach such topics?

Cheers!

Oskar

p.s. Ukraine is still under brutal Russian invasion. A lot of Ukrainian people are hurt, without shelter and need help. You can help in various ways, for instance, directly helping refugees, spreading awareness, putting pressure on your local government or companies. You can also support Ukraine by donating e.g. to Red Cross, Ukraine humanitarian organisation or donate Ambulances for Ukraine.